What happens when big businesses knock off local designers?

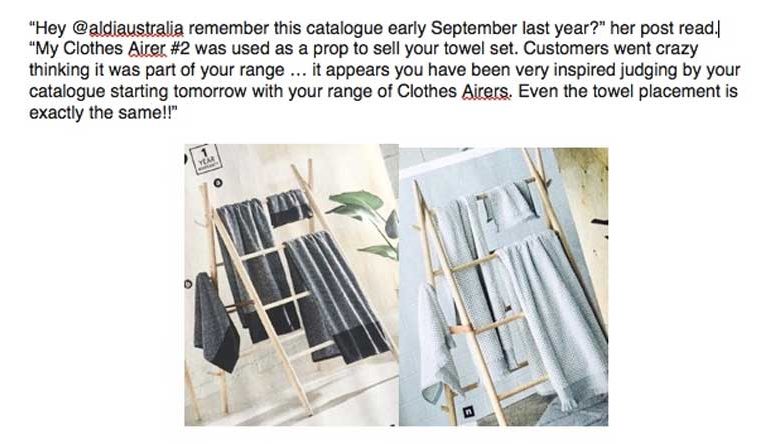

When a major retail chain advertised an identical product to one they’d borrowed for a photo shoot from a small Melbourne brand, it’s no surprise the internet went wild.

David vs Goliath scenarios like this underpin how inadequate Australian intellectual property protection leaves furniture designers at risk to counterfeiters.

It’s when big businesses cherry-pick best sellers for profit, and astoundingly the law lets them do it. This happens all the time, so it’s not hard to guess who ultimately loses.

**The original post 14 July 2018, updated August 2022 to include recent legislation changes**

ROBBED ON HOME TURF

Discount retailer Aldi featured a product by Miss Glass Home as a photoshoot prop for their catalogue, the clothes airer styled with Aldi bath towels set to feature in their next campaign. Customers assumed the clothes rack was for sale and flocked to social media to ask for pricing and availability.

A few months later, Aldi announced a new $69.00 clothes airer online. You guessed it, one that mimicked the Miss Glass Home airer that had been used in the earlier photoshoot.

IMAGE // @missglasshome Instagram

IMAGE // @missglasshome Instagram

“Make your own towel rack but don’t take the unique details away from a small Melbourne furniture designer like me.

There’s room for us all to run our businesses without having to step on each others toes.”

Miss Glass Home, Instagram

We spoke with Siobhan from Miss Glass Home, who was devastated that such a big retailer had been so blatantly knocked off her first furniture design.

Miss Glass explained that their brand ethos centred on ethical, sustainable products, and the clothes airer was their first foray into product design, so, being ripped off by a discount retail network added extra sting to the punch.

DOES THE LAW PROTECT FURNITURE?

Because Siobhan had not filed a design registration with IP Australia, she had no legal recourse.

At the time, unlike most of our trading partners, there was no ‘grace period’. Unlike our many trading partners, Australia had no 12-month buffer zone where a product can be shown publicly with certain protections prior to the product applying for design registration.

This meant because the clothes airer had already featured widely in print and across social media, there was no possibility to register the design. Back then, an IP Australia prerequisite for design registrations required products to not appear in the public domain. This included social media, exhibitions, magazines and blogs.

** EDIT // As of March 10, 2022, Australian designs now have a 12-month ‘grace period’ or protection before the design is registered.

The Authentic Design Alliance collaborated with industry bodies and government agencies for six years to lobby for this first significant amendment to IP laws. Further amendments are pending in the next two to three years.

Affecting real change is a long game. Read more HERE

ALDI TIMBER STOOL RECALL

But the drama didn’t end with the clothes rack. Fast-forward ten days from that online announcement to when Aldi catalogues landed in inboxes around Australia.

This coincided with a product recall announcement on the Aldi Facebook Page for a stool shown in the same image as the clothes rack.

Commenters suggested the advertised $69 Aldi stool resembled an $800 Eggcup stool from furniture retailer Mark Tuckey.

Now it can be acknowledged that simple geometry doesn’t always lead the way when it comes to originality. Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi produced similar forms during the 1920s and 30s, and prior, turned timber stools had long existed.

EGGCUP Stool sold by Mark Tuckey

But back to Aldi-gate!

The story of the copied clothes rack was sadly buried from this point, as news reports focussed on the cheap timber stool and its link to the popular Tuckey product.

An unfortunate outcome as the Mark Tuckey retail network was well established and hugely successful, and the focus on the real tragedy – a small studio having their only product copied – was lost.

Aldi (Facebook)

Adding to the drama, the timber stool was cancelled the day prior to launching. A few that remained were allegedly removed from shopping trolleys by Aldi staff in-store, and customers raged on this Aldi FB stream.

Aldi cited ‘production issues,’ and the brand said via Facebook that ‘the production issue (related to) Australian Quarantine’ and the stools need ‘further treatment before it could be sold in stores.’

DESIGNERS FALL THROUGH THE CRACKS IN DESIGN LAWS

Miss Glass Home supporters commented online the retailer had infringed the brand’s copyright, which isn’t the case in Australia.

Products need to be registered with IP Australia, with a ‘design registration’ being the only real defence against copycats. A design registration is granted once a product is determined to be ‘new’ and ‘distinctive’.

Once granted, the registration granted a ten year protection period. Five-years renewed by an additional five years. Not nearly long enough for a designer or brand to recoup rightful profits from their original idea, R&D and marketing investment.

So had the Mark Tuckey stool been a registered design, given it launched in 2006, any protection (if it had) would’ve have by then lapsed!

WHAT ABOUT COPYRIGHT?

Copyright doesn’t apply in this instance.

In the USA, copyright is a viable and effective form of protection against knock-offs. Defending furniture copyright infringements in North America is typically solved by a cease and desist request. And the copyright application is a straightforward and inexpensive process.

In Australia, photography, art, music, film and literature receive free and automatic copyright protection.

Yet three-dimensional objects like furniture are not covered by copyright protection. And it’s difficult to understand why industrially produced designs like furnishings are treated differently from other creative disciplines.

“Spare a thought for creative small businesses who rely heavily on a small range of products to pay our rent and put food on the table for our families.

You know we can’t compete with you, and this is exactly why you do it.”

Miss Glass Home, Instagram

NO-WIN SCENARIO

It’s not just the designer who loses out on design theft. Everyone associated with creating, making and distributing the original product loses out financially, emotionally and more.

Copies are typically cheap imitations; everyone suffers reputation damage when customers mistake poor-quality copies for the real McCoy.

It’s a lose-lose scenario. One that the ADA strives to rectify, but changing laws is a very long process.

And changing consumer behaviour away from the culture of what we call ‘disposable decorating’ or ‘throwaway-ism’ is an even bigger job.

Society has been conditioned to want the cheapest product immediately. A purchasing behaviour that fuels the downward price spiral. One where quality is lost in the process. This encourages retailers to continue to sell low-value, short-life products. Products that ultimately end up in landfill.

Join us, follow us and support us to help educate about why choosing well and buying once is a social responsibility.

Knowing who makes the products you buy. What they’re made from. And knowing these products will endure – is what connects us to things we want to keep. Repair. Restore. Or even resell so that someone else can enjoy them.

This is not the culture the chain store mentality supports.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

SUPPORT THE ADA

Become a Member // learn more HERE

Follow us on Instagram @authentic_design_alliance

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

LEARN MORE

Read more here on the DIA Design Institute Australia statement and report from NEWS.com.au, and more here on how Aldi customers are frustrated by being ‘baited’ by the ‘special buy’ advertising techniques

READ More Case Studies // The Building Industry Problem taking original furniture specs and swapping them out for cheap copies of local designs

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

SUBMIT CASE STUDY

We welcome case study submissions that help us understand the implications of design theft in Australia.