Some of Australia’s best-known rock photographers claimed copyright infringement by an online auction of media giant Fairfax’s Sydney Morning Herald image archive.

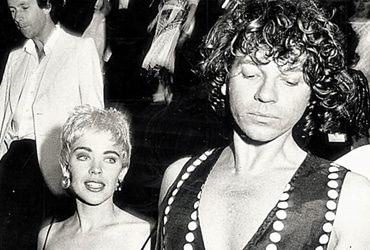

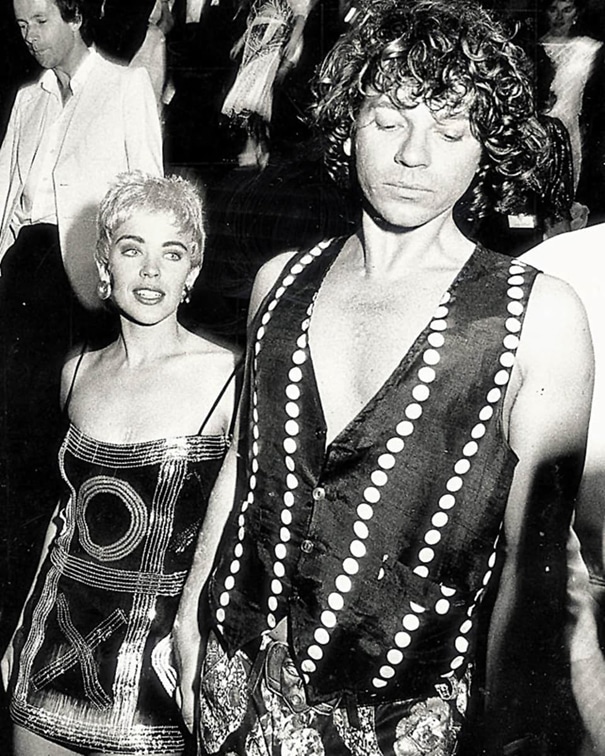

ABC news reported hundreds of original photographs that include Michael Hutchence and Kylie Minogue (in that noughts and crosses dress!), Cold Chisel, Midnight Oil and many more iconic Australian and international rock musicians – were to be sold online through Lawsons Auction house.

Long story short – in 2013 Fairfax outsourced digitising their image archive to a US company that went broke and 2 million prints from the Sydney Morning Herald fell into the hands of the LA art dealer, who subsequently put them on sale in Australia.

Kylie Minogue and Michael Hutchence, one of the works that photographers disputed should not be permitted for sale in the online auction. Image: Jack Atley

Finding multiple copies of their work in the auction, photographers took to Facebook with a string of WTF comments. Legends Tony Mott and Ian Greene claim in the thread they not only retain the negatives to the images, but are the rightful copyright owners.

Adding insult to injury – the images were republished, again without photographer permission, in many cases, with no author attribution or credit in the auction catalogue.

Photography – images taken after 1955 are protected for the life of the author plus 50 years after their death

Like art, photography is automatically protected by copyright in Australia. Whilst the length of protection has changed over time, images taken after 1955 are currently protected by copyright for the life of the creator (author) plus 50 years after their death.

Film, music, photography, art, literature and architecture are automatically protected by copyright, but not furniture and lighting – why?

Like many areas of IP (Intellectual Property) there’s no one size fits all answer. Arts Law Australia cautions that photographers might be “infringing copyright if photographing the whole or a substantial part of a literary, musical, dramatic or artistic work, if the work is still protected by copyright.“

This references other creative disciplines also protected by Australian copyright, but not three-dimensional industrially designed products. Which begs the question – why is design treated differently to other creative disciplines with regard to automatic copyright protection?

“A successful product creates a network.

A successful collection creates a sub-economy”

AMS, Authentic Design Alliance

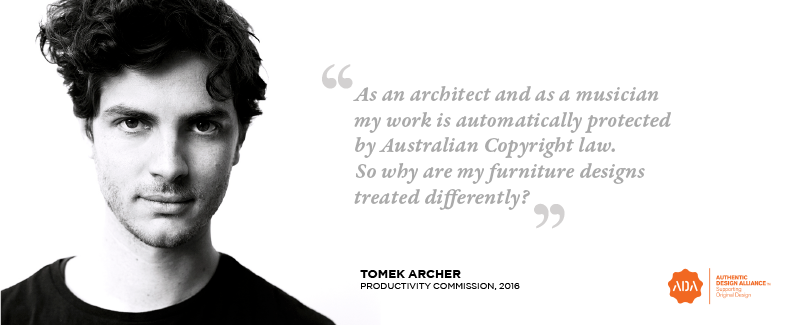

Sydney designer Tomek Archer supported the Authentic Design Alliance campaign during the 2016-17 Productivity Commission Inquiry into Australian Intellectual Property law (PCIP).

Having previously spent a decade as a touring and recording artist in the band Van She, Tomek is also an award-winning furniture designer and architect.

Archer asked the Commissioners a simple question – if as an architect or a musician his IP is automatically protected by copyright in Australia, why are his furniture designs treated differently?

“The design industry is 20 years behind the music industry when it comes to dealing with digital rights, and much further behind when it comes to copyright protection!”

Tomek looks to the music industry who were forced to adjust licensing models once streaming and digital purchases became the norm. They had to adapt when new distribution streams appeared.

By this reasoning, Archer questioned why the design industry is yet to address the problems that have arisen with online product sourcing, pointing to search engines like Google who compound the problem by making cheap copies easy to find or allowing replica retailers to cheat by using key words to push their knockoffs to the top of search engines.

In his presentations with us at the PCIP hearings, Tomek asked the Commissioners to refer to the het Productivity Commission draft report on their table. He noted tat each page of the PCIP report clearly labeled as protected by Australian Copyright law.

It was a watershed moment for the room.

In short, Tomek pointed out it is illegal to reproduce the PCIP report without written permission from the Federal Government or accreditation, yet legal replicate furniture that isn’t design registered.

Extract from IP Australia report ‘Talking Design’ (December 2019)

With no automatic copyright protection, that just leaves design registration…

Currently industrially produced objects like furniture and lighting can only be protected in Australia by registering designs with IP Australia, and once granted, protection extends for a mere 10 years!

The process is costly, and most designers create a collection of products, vs just one product, bulk registrations incur multiple filing fees, and when granted, the registration is 5 years renewable for an additional 5 years (10 years total).

Given the extensive financial investment essential to launching any collection, 10 years is simply not enough to recoup a rightful income via product sales!

Things become more complicated if a registered design is copied – as most

What happens to registered furniture designs after 10 years?

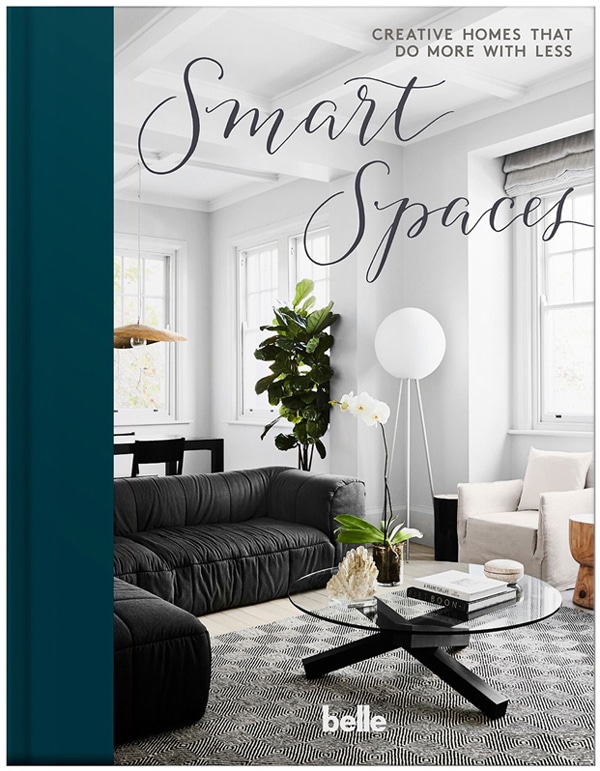

CAMPFIRE by Tomek Archer consists of four components that assemble without fixings and glue. Having won numerous awards, once the design registration expired the replica industry pounced.

Tomek is one of many Australian designers to discover copies of his work. The best-selling Campfire table has received many accolades, including being nominated in the Top 20 Australian Design Moments and listed alongside the Holden Monaro and designs by Marc Newson by AFR Australian Financial Review.

Archer registered the Campfire table whilst still studying, and given his music industry background, unlike many early career creatives, Tomek was acutely aware how critical protecting IP is to his future income streams should his product become commercially successful.

In most industries that would be considered theft.

But not in the design industry……

Almost immediately the Campfire 10-year registration expired, a known replica retailer announced on social media ‘what do you think about our cool new table?’

Yep, you guessed it – no registration, no protection, so legally the design was up for grabs for anyone to produce, sell and profit from!

What followed was the first major online take down in Australia of a local design via social media. An ADA-led rally sparked a lengthy comment stream by informed objectors that spanned designers though industry leaders.

Within 24 hours the brand conceded that they didn’t know the design was an original Australian design, and pledged to remove their knockoff from sale.

In what appeared to be a classic case of a buying team sourcing products without any due diligence or knowledge of the provenance of the design. So if the buyers are ignorant, what hope do their unassuming customers have when it comes to accurate information about what’s real and what’s fake?

CAMPFIRE by Tomek Archer featured on Belle Magazine SMART SPACES. Image : Bauer Media

Creatives investing in lawyers not new products

Unfortunately the example above remains a ‘one-off’ and the rest of the industry are left to fight for their rights through legal channels. For most this is an unaffordable reality, so it’s a lose-lose scenario.

It makes us wonder why do creatives and the brands that invest in representing them have to resort to expensive legal action?

And why are no laws in place to protect the future growth of the furniture and lighting sector?

Meanwhile – the UK introduced automatic copyright for the life of the creator plus 70 years after their death (life plus 70) – retrospectively protecting iconic designs targeted by replica resellers

In 2016 the UK introduced radically improved IP protection for the furniture sector to align with Europe. Copyright was extended from 25 years of a product first hitting the market – to life plus 70 – now protecting works for the life of the creator plus an additional 70 years.

This meant that the many iconic designs feasted on by the replica and counterfeit design industry are now protected by UK copyright. The new laws go as far as levelling penalties of up to £50,000 and 10 years jail!

So back to the rock photographers….

It will be interesting to see how the scenario plays out. It appears to be multi-layered and complex, despite photography being one of the easiest creative disciplines to defend when it comes to copyright, it will get down to a legal determination of exactly who is the rightful copyright holder.

Ironically, with furniture and lighting, photographic copyright is usually the simplest, least expensive way for designers (and their distributors) to remove copies of original designs from unauthorised online sales portals. Often it is the ONLY recourse…… unfortunately.

GLISSANDO Credenza by Jon Goulder, available Spence and Lyda. A global selling platform used this image to sell copies of the extremely limited edition work in large quantities for impossibly low prices. Defending his copyright, Jon’s photography was removed. Image: Bo Wong

Photographic copyright in the furnishing sector

Jon Goulder is one of many local designers to discover knock-offs of his work listed on global marketplaces such as Amazon.

A fourth generation craftsman, Goulder pieces are held in prestigious collections including National Gallery Australia and many private collections, and naturally he was outraged!

At the time we contacted Jon to flag that either he or his photographer owned the copyright to the images used to sell the fakes. Taking ADA® advice to hand, they successfully used the platform’s dispute resolution forum to achieve immediate removal of their photography from the site.**

Whilst removing copyright protected images might minimise the ability for counterfeiters to knock-off original designs, it’s not the ultimate solution. But presently it’s the most affective option!

**Footnote – it’s essential to continue to check periodically the images are not reposted.

AFR Magazine Authentic Design feature by Stephen Todd exploring Australian designers being ‘savaged by counterfeiters’. Image: Authentic Design Alliance Instagram

Is design registration the answer?

Ultimately it’s time Australian lawmakers up their game and protect our thriving furnishing sector. A sector currently savaged by the replica industry and counterfeiters thanks to lax IP laws.

Retailers, distributors and manufacturers like Cult and Tait now design register all the locally created designs they produce and sell.

Kate Stokes from Melbourne Design Studio Coco Flip tells us that chasing all the copies of her award-winning Coco pendant would be a full-time job. It was her first product, and she had no idea it would become a runaway commercial success. Not being registered, the design is legally on the table for knockoff merchants to peddle cheap look-alikes!

So the struggle is not just real, it’s expensive. With legal advice and court action not only cost prohibitive, defending rights in the courtroom takes businesses away from their core function of creating, making and distributing quality, original products.

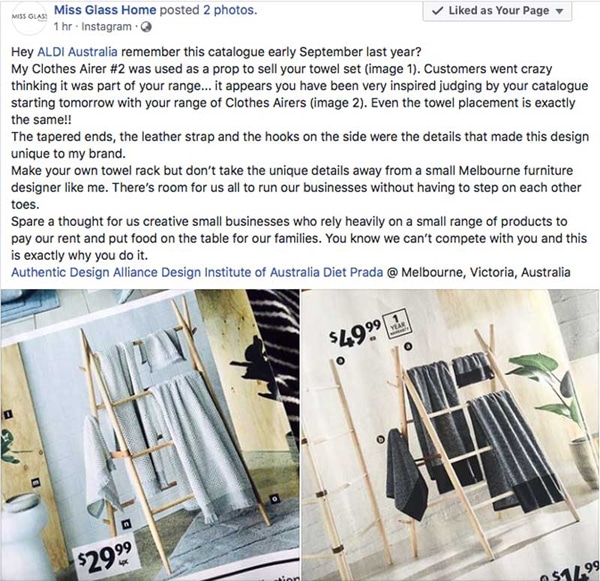

Image: Miss Glass Home Facebook

ALDI vs Miss Glass Home

Like Kate, Siobhan Glass from Miss Glass Home had her first product knocked-off. Both designers had no concept their first product would become so popular.

It’s worth drilling down comments stream for the ADA post for a clear picture of industry reaction.

When launching their products neither Kate or Siobhan knew about design registration.

Even if they wanted to register, they couldn’t c/ the IP Australia requirement that prohibits products exhibited or published, inclusive of blogs and social media from being registered.

This absence of ‘grace period’ is pretty much unique to Australia. Most of our trading partners have a ‘grace period’ of 6 months or typically 12 -24 months – that allows products to be refined prior to requiring registration.

A win for the chain stores, a loss for the creators.

Extract from IP Australia report ‘Talking Design’ (December 2019)

Originally published by the ADA® October 28, 2018 // Updated March 2020.

/////////////////////

Support our change campaigns – Join the ADA!

With support from our affiliated partner Australian Copyright Council, the ADA® is poised to launch a national campaign for increased IP protection for the furnishing industry. More on that very soon.

In the meantime – if you care about supporting change – become an ADA® Member?

Memberships directly fund our advocacy and education.

Head HERE (desktop / laptop) or HERE (Mobile / Device)

/////////////////////

TAIT, CULT, SPENCE & LYDA and ANIBOU are Authentic Design Alliance® Premium Members. HELP STOP DESIGN THEFT and join the ADA® today!

/////////////////////

READ MORE about the AFR article by Stephen Todd.

READ MORE about the Miss Glass Home Case Study or Coco Flip Case Study

/////////////////////

WANT TO CHAT? – CONTACT US

/////////////////////